Marine videographer and biologist Sophie Hansa has spent the past few months putting her knowledge of science to use on the strange world of Stormwrack, solving seemingly impossible cases where no solution had been found before.

When a series of ships within the Fleet of Nations, the main governing body that rules a loose alliance of island nation states, are sunk by magical sabotage, Sophie is called on to find out why. While surveying the damage of the most recent wreck, she discovers a strange-looking creature—a fright, a wooden oddity born from a banished spell—causing chaos within the ship. The question is who would put this creature aboard and why?

The quest for answers finds Sophie magically bound to an abolitionist from Sylvanner, her father’s homeland. Now Sophie and the crew of the Nightjar must discover what makes this man so unique while outrunning magical assassins and villainous pirates, and stopping the people responsible for the attacks on the Fleet before they strike again.

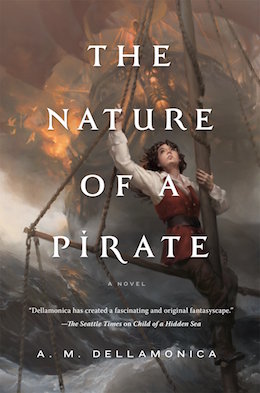

The Nature of a Pirate is the third book in A.M. Dellmonica’s Lambda Award nominated Stormwrack series. Available December 6th from Tor Books.

Chapter 1

Kitesharp was bleeding.

The wounded ship was fifty feet long, with a crew of fourteen sailor- mechanics, and when dawn rose over the Fleet of Nations, her blood trail was just a thin line of crimson threaded into her wake. It twisted against the blue of the sea, a hint of pinkish foam that might have gone unnoticed for hours if it hadn’t begun attracting seabirds and sharks.

The whole Fleet watched as the birds shrieked and Kitesharp’s captain raised a warning cone up her mainmast. Soon—presumably aft er her bosun had been below for a look—a sphere was raised, too. From a distance, both cone and sphere would appear as flat shapes, seeming to onlookers to be a triangle and circle. It meant Ship in distress. Help required.

This particular distress call had gone out twice before.

By midmorning the blood trail was a foot wide and the ship had taken on enough water to raise her bow well above the surface.

The greatest of the Fleet rescue vessels, Shepherd, was ready. Her crew brought her alongside the craft as traffic flowed past. Working with military precision, Shepherd’s crew lowered a walking bridge to Kitesharp’s deck and boarded personnel: twenty workers, first, to help the crew load the doomed ship’s tools and fixtures, to strip whatever they could. Yards of hang glider silk were waiting to be off-loaded, along with the flexible boards that made up the skeletons of the gliders’ wings. There were bright streamers that carved the kites’ paths through the sky, above the sails of the Fleet, and pots upon pots of dyes, glues, and needles. Everything that wasn’t bolted down, including the sailors’ personal trunks, was already packed.

Shepherd also brought soldiers, fit young adults bearing stonewood swords and a grim sense of purpose. They would search the boat from main deck to bilge, looking for intruders. They brought a spellscribe, who was tasked with seeking anything that might tell them about the intention—a curse, some whispered—that had been worked upon the vessel.

For this third sinking, they also brought Sophie Hansa.

Raised in San Francisco and trained as a biologist, Sophie had been working as a marine videographer until she fell into… Well, she was essentially applying twenty-first-century science to puzzles the locals couldn’t work out, here on Stormwrack. She had come in search of her birth parents, following them to a society that lived largely at sea, on a world whose existence had been concealed from Earth.

Since then, she’d done everything from hunting for a newfound aunt’s murderers to determining international owner ship rights over a species of migrating turtles.

The locals were strangely hampered by a cultural taboo against curiosity. Sophie had realized that her best chance of being allowed to stay was by channeling her natural desire to ask questions in ways that earned her political goodwill.

Lately she had been mining the judiciary’s warm case files, seeking out little mysteries that might be cleared up with a bit of fact-finding or a basic application of science.

But now someone was sinking small civilian ships that followed Stormwrack’s Fleet, the great oceangoing capital city that circled the world, keeping the peace and policing piracy. Knowing the sinkings were caused by magicians wasn’t helping the authorities. So, here was Sophie, in her wet-suit, with her tanks and camera and a solar-charged LED lamp, about to take an exploratory plunge through a sinking ship.

“What will you need from us?” asked the head of the Shepherd rescue crew, a twentysomething woman, Southeast Asian in appearance (although that meant little here, on this world of tiny island nations), named Xianlu. She was all business. “Kir Zophie?”

Right. Concentrate. “Ship’s already taking water—do you know where it’s coming from?”

“The aft hold.”

“I’ll start there, before it gets any deeper.”

The officer summoned one of her crew, a broad-shouldered guy with the build of a high school quarterback, clad in a tight-fitting uniform designed for swimming. He looked familiar; after a moment, Sophie realized she had seen him at a disastrous Fleet graduation ceremony she’d attended after she had first arrived here, in the spring, eight months ago.

“Escort Kir Zophie below.”

He bobbed his head in assent and gestured for Sophie to follow.

“Get the sails down, move and double,” Xianlu ordered, turning her attention to the crews waiting at the ropes.

Kitesharp had a high, snub profile in the water that reminded Sophie of a modern towboat, despite her sails and rigs. Her bow was tilting up as she continued to take water in the stern.

“What’s your name?” Sophie asked the boy as they worked their way past a work crew busily sealing the tins of hang glider dye.

“Tenner Vale, Kir.”

“Tenner” was a ranking for cadets. It meant he had a full ten years left on his term of service. “Graduation was a while ago, wasn’t it?”

He nodded. “In four months, after my exams, I’ll be a niner. Xianlu is a septer.”

“Do you stay a tenner if you fail the tests?”

He did a double take, prob ably thinking, How can you not know that? Then, having apparently decided she wasn’t joking, he said, “A de cade is a de cade. Niners who’ve failed their exams are given posts with less responsibility.”

“Drop and stow, one, two!” The crew lowered the mainsail. The canvas and rigging loosened and fell to the deck with a sound like a hundred drumbeats. The ship had already been given up for lost. Kitesharp, but for the ropes that bound her to Shepherd, was now at the mercy of the waves.

“Like a wounded animal,” Sophie murmured.

Vale looked frustrated, almost ashamed. “We would fight to save her, if we understood how she’s being sunk.”

They had to be desperate to turn to me, Sophie thought. Stormwrackers were ambivalent about science. Much of it they labeled atomism and dismissed as unreliable, even dangerous. People preferred to believe in a patchwork of disciplines with as much merit as astrology or dowsing.

Wrackers could navigate ships by the stars. They built and used barometers. But they also thought that observing the flame from a yellow candle would tell them the emotional state of a prevailing wind, and that aspirin worked by “encouraging the spirit to bend like a willow around its hurts.”

Sophie was getting away with working for the courts by rebranding her skills. What she was bringing to the table wasn’t atomism at all—that was the story. It was a shiny new discipline dubbed “forensic.”

Same old wheel, shiny new rim.

Vale opened a hatch, revealing a ladder. Giving him what she hoped was a reassuring smile, Sophie stepped into the hold. The tilt of the ship was more obvious here; she crab- stepped her way down the inclined deck and opened another hatch, peering into a flooded chamber.

“Thanks.” She put on her flippers and descended alone. The hold was half full of waist-high salt water. She took a careful stance on the deck, set her light, and began filming, taking a shot of the whole room first, just in case. She captured everything visible above the waterline.

“It is water,” she noted.

That look again: of course it’s water. “Your pardon, Kir?”

“The ship’s gushing blood, but filling with salt water. There’s no blood here, so where’s it coming from?”

He gave the half shrug, a bob of shoulders that was the unofficial Wracker ward against curiosity.

Having filmed it, she took time to look with the naked eye. “You know if anyone has schematics for the ship? Plans?”

“I believe so, Kir.”

“To work out how fast the water’s coming in, we’ll need an accurate measurement of cabin volume.”

“A sailing master can do the calculations, if it’s important.”

She didn’t bother to say that, with the right measurements, she could do it herself. “While I’m down there, I want you to record how long it takes the water level to rise from here…” She put her hand on one of the ladder rungs. “To this one. Do you understand?”

He made a gesture, indicating rising water. “Sink rate per ten count?”

“Exactly. Do you have something that counts seconds for you?”

Vale nodded. “And a measuring rope, Kir.”

“Good. As accurate as you can, please.” She set her watch to record the diving time.

“Understood, Kir.”

Something in his tone made her think of Captain Parrish; she felt a pang of something that was equal parts longing, loneliness, and frustration.

Forget Garland. It’s time to focus on the not-so-smart dive of the day. Still with a hand on the ladder, she checked her camera’s waterproof housing, put on her mask and rebreather, took a few breaths, and then bent her knees to bring her face below the level of the rising water. Shining the light around the narrow space, she looked for floating debris or loose rope—anything that might knock or entangle her. But the crew had worked upward from the compromised stern when they began emptying out their ship; the space was empty. Sophie half swam, half crawled to the low point, camera and light at the ready.

She hoped to find a gaping hole in the hull, of course, something to account for whatever was hemorrhaging into the seas behind the ship. But at first glance, there was nothing. No hole, no bubbles, certainly no blood.

Nothing to patch. If she could be patched, she could be saved.

The answering thought came in her brother’s voice: If it had been easy, they wouldn’t have asked you to help, Ducks.

Taking out a bulb filled with blue-black squid ink, she squeezed out a drop, then another, working her way along the floor. The first two drops swirled lazily. The third moved and dispersed, propelled by a current coming up from the boards.

She put out a hand, discovered the pressure of inrushing water, and worked her way toward it, seeking its source by touch.

Here, on the hull. She pushed in close. On the wood there was a waxy mark, dark red on the oak boards, barely visible.

It was the outline of a hand.

She held her position, working the light and camera together to get a decent shot of the outline. It was biggish, with a stubby, truncated pinkie.

The red looks waxy, like crayon, she thought.

Releasing her camera—it was tethered—she dug into her tool kit again, selecting a steel scalpel she’d imported from home. Working carefully, she tried to scratch some of the waxy stuff into a test tube. It didn’t want to come.

She tried again, pushing harder. If she could pry up a splinter of the wood…

Softness, like flesh.

The blade broke a chip of the wax-marked wood loose, but the force of Sophie’s hand drove it inside the outline of the hand. Instead of glancing off of more wood, it dug into something with the give of meat.

All at once, the outline came to life, fingers flexing blindly to grab at the scalpel. As it did, the hull gaped and cracked. A surge of cold water pushed inward. The back of the hand, the part that had been outside the ship, was covered in shreds of bloody tissue.

Like Cousin It from the Addams family. No, It’s the one with all the hair. Like Thing, just a hand—eww, hand—but grab that splinter…

Sophie caught the chunk of wood with its wax smear, tucking it into her sample tube. Kicking, she put some space between herself and the hand. She reeled her camera back, aimed the light, and started recording video.

The incoming water had more force now. She could feel it gushing past, the sensation reminiscent of water jets in a hot tub. As the hand curled in, leaving a deep, five- fingered hole in the hull, Sophie’s diving light picked up barnacles, streamers of seaweed, and gory, spongy-looking masses on the back of the hand, the side that had been in the water.

Sophie snagged a hunk of red tissue, too, clipping it into another specimen flask without taking her eyes off the hand.

The outline on the boards was growing now, the drawn edges of the wrist extending as if someone was there, drawing in both lines with crayon. The hand grew a wrist, then a forearm. It bent at the elbow, and the boards of the hull reshaped themselves into an arm. It lashed about as it groped at the inside of the ship.

Sophie swam farther back. The thing, as it detached itself, was ripping ever- greater holes into the bottom of Kitesharp.

What happens when it grows a head?

It’d be dumb to wait around and find out, wouldn’t it? She kicked back to the ladder. The tenner, Vale, was timing seconds and measuring water rise.

“Anything, Kir?”

She spat out her rebreather. “Found a monster! Up, up!”

A shudder ran through the ship, accompanied by a sound of splintering wood so loud it drowned out Vale’s reply. He offered Sophie his hand.

The incline of the deck grew more steep by the minute as they charged to the nearest ladder out of the hold.

“You first, Kir.” The kid drew a shortsword.

Sophie fought an impulse to argue. What was she going to do, fight a monster in her diving rig?

Another splinter. The deck below them cracked, splitting up the middle. The ship listed sharply to starboard.

“Teeth!” Vale cursed. “Ship’s cross-cut!”

They scrambled out onto the deck.

The blood slick around Kitesharp had become a dense red puddle, a crimson smear broken by tissue and bits of debris. Shark fins stirred in the murk. A boarding plank, extended from Shepherd, was stretched across the gap between the two ships. A half-dozen of Xianlu’s crew stood ready, waiting for Sophie and her escort.

The ship began to buck, as if something big had taken hold and was shaking it.

“There!” Sophie pointed, as the wooden hands rose to the main deck, one after another, the leading edge of a wooden body covered in gore and seaslime, pushing up through the hatch as if it were forcing itself through a birth canal.

“Wood fright!” someone shouted.

“This far asea? How did it seed?”

The deck heaved. The hatch broke in zigzag fissures. As the hands came down onto the deck they seemed to stick—roots grew from the wooden palms into the planks, and the fright had to rip them out, causing more damage.

It did not breathe. A person would have been panting with effort, but this, whatever it was, had the eerie stillness of a store mannequin.

Sophie trained her camera on it as it raised its head.

Are its eyes covered in moss?

The thing began to stride across the crumbling deck of Kitesharp, ripping holes in the boards as its feet fell and rooted, rose and tore loose. It made straight for Shepherd.

Sophie could feel the bridge underfoot moving as they pulled away. Vale and Xianlu were guiding her so she could keep filming and still move backwards in her flippers. Unless the thing could jump a hell of a long way—Why couldn’t it?—there was no chance it’d catch them.

“Someone called this a wood sprite?” Xianlu asked.

“Wood fright, Septer,” someone else corrected. “Used on Mossma, before the ban, to guard forests. And for murders, sometimes.”

“Frightmaking’s illegal,” Vale said.

“I said before the ban.”

“Was anything like this aboard the other ships?” Sophie asked.

“If so, it sank with them,” Xianlu said.

“I think I woke this guy before he was fully baked,” Sophie said.

It was a guy; the body was unmistakably male, and on the slender side. He had a limp.

A limp and… a foreshortened pinky? She zoomed in on its hands.

The thing began to run toward them.

“Gunner battery one! Fire!”

Stormwrack didn’t have cannons. They used magically transformed specialists instead. Three sailors stepped up and hurled flaming spheres at the wood fright.

It pulled up short, throwing both arms up to defend its head—giving Sophie a good shot of all ten fingers—and then disappeared in a burst of fire, leaving an appalling stench of scorched meat and campfire behind.

As the smoke from the cannons dispersed, the remains of the sailing mechanics’ shop, Kitesharp, fell to pieces and vanished beneath the waves.

Chapter 2

Dear Bram:

So I’m sitting on Constitution, waiting on the boss lady to get around to seeing me and hoping to convince her to go forward with our fingerprint project. She might acquaint me with some divers, so that I can find a partner. They’d be mermaids—how cool is that?

I haven’t found anything to conclusively indicate whether Stormwrack is some radically altered far future of ours or a parallel dimension. I’m still hoping we can send archaeologists to a site on land where something famous has been found at home. There’s an island near the latitude/longitude of the Valley of the Kings. We could try to talk someone into searching for King Tut’s tomb. If all that stuff Lord Carnarvon and Howard Carter dug up in 1922 was waiting, underground—that would definitely prove we’re in a parallel world, right?

It would be tricky—what isn’t tricky here? We’d need someone with expertise who wanted to dig them, not to mention permission, but it’s the best idea I’ve had so far.

Figuring out whether Stormwrack was simply the future was important, because whatever had wiped out or submerged most of the Earth’s continental landmass had obviously been devastating. Was their home staring down the barrel of a bunch of massive comet strikes? The chances of those hypothetical strikes happening within their own lifetimes was vanishingly small—she and Bram estimated a ten-thousand-year window for such an event—but neither of them could let go of the possibility.

How are Mom and Dad doing? Did you give them my letter? You haven’t said—

“Kir Sophie?”

She looked up from the letter she was writing into the impassive, big-eyed face of a government functionary from the nation of Verdanii. “Hi, Bettona.”

“Convenor Gracechild will see you now.”

Annela Gracechild was part of the government of the Fleet of Nations, a congress of two hundred and fifty sovereign countries, island nations clinging to the archipelagos of land that remained within the enormous seas that covered most of the world.

Sophie hadn’t set out to abandon ordinary life in San Francisco, to forge a path, alone, on a strange world. But six weeks earlier she’d been given a choice: stay, now, and make a place for herself… or never come back.

Stormwrack’s very existence was a whopper of a scientific discovery. And given the lingering chance that it was Earth’s future, that a disaster was on the horizon… Despite the risks, she’d stayed.

Her brother had returned to San Francisco to follow up their research into the connection between Earth and Stormwrack and—just as important—to ensure their parents didn’t report them both missing.

As for Sophie’s half sister, Verena, and the crew of the sailing vessel Nightjar: Annela had sent them off on an unofficial diplomatic mission.

Sophie had been working to endear herself to Annela, who clearly had veto power over Sophie getting the Stormwrack equivalent of a green card. Agreeing to poke into the serial attacks on the Fleet’s civilian ships had seemed, at the time, like a good way to make her case.

It hadn’t occurred to her that she might fail.

Now she got up, exchanged bobs with the assistant—she was getting better at the Fleet bow—and followed her belowdecks to a cabin that looked, to Sophie, like an autumn-colored bordello. Orange silks hung from the walls, hiding the boards. Dark-brown cushions, embroidered with fallen leaves, covered most of the surfaces.

Annela Gracechild lay at the center of the nest. She was in her sixties, tall and curvy, with copper skin and so much self-confidence it barely left room in the cabin for air.

“Welcome,” Annela said, declining to rise. Bettona set out a tray—tall cylindrical cups of thrown pottery, a steaming pot of anise- scented tea, and a plate of fresh-baked apricot biscuits and salted walnut sticks that reminded Sophie of pretzels. One of Bettona’s cuffs was dusted with flour, hinting she had done the baking herself.

“Sit, girl.”

Sophie said, “Are you sick?”

Annela gave her a flat look that might have meant anything from Thanks a lot for saying I look like crap to Not in front of the servants, dear.

“Fasting,” she said. “Now, what of Kitesharp?”

Sophie filled her in on the morning’s events, holding out the camera so Annela could see the wooden fright with its mossy green eyes. “I’m not sure how much I can offer—it’s obviously magic at work.”

“Reminds me of the salt creatures you fought on that bandit ship, Incannis,” Annela said. “Short lived, somewhat mindless, used for mischief—”

“This one can’t cross the deck of the ship without rooting into the wood,” Sophie said. The tea wasn’t the usual, she noted—the anise flavor was strong. “If a thing like this has an intended habitat, I’m guessing this isn’t it.”

Annela nodded. “Yet tearing apart the ships’ hulls and sinking them seems to be the point.”

Sophie braced herself for a reprimand for having hastened the ship’s demise. When none came, she went on. “The drawn outline of the hand is off—there’s something wrong with the little finger. I suggested Septer Xianlu have a glance at all the Kitesharp crew.”

“In case someone’s missing a digit?”

“And walks funny. The fright had a limp.”

Annela looked at Bettona, who made a note.

“I also have a sample of the waxy stuff. It might be testable.”

“Your brother can send you instructions for performing an alchemical knowing, can he not?” Annela asked.

“Chemical identification,” Sophie corrected. “Maybe. If the supplies exist here. There’s also this.” She held up the plastic container containing the bit of bloody tissue, preserved in denatured alcohol. “It’s gross, but I wonder if this might not be uterine tissue.”

Annela looked it over. “Looks like it. I suppose there’s no way to be sure.”

“There might be,” Sophie said. There’s no way to be sure was rapidly becoming her least favorite phrase. “I’ll need to talk to a doctor.”

“An outland doctor?”

“You must have obstetricians here,” Sophie said. “The whole thing had an icky birth vibe to it. The blood trail, the way the fright pushed its way up through the ship—”

“The Fleet decries frightmaking; there was an international effort to stamp out the known inscriptions, perhaps fifty years ago. There’d been an incident, on Tug Island, I believe. Thousands of them, running riot.” Annela handed back the sample. “I seem to recall the spells require a subject, someone to provide a…” Her hands moved, shaping a figure.

“A template?”

“Yes.”

“Is there anyone who’d know?”

“You could ask that last bandit from Incannis, the one who attacked you. He’s aboard Docket, awaiting trial,” Annela said. “Request a visitor’s pass from the judiciary.”

Sophie nodded without enthusiasm. Her birth father had captured the sailor in question, while slaughtering all of his crewmates. She could do without any hard reminders of that particular bloodbath. “Yeah. Or… is there a listing or index of spells? Something that would talk about fright-making?”

“Perhaps some trial minutes persist, from the cases related to the effort to eliminate the practice. You want your pet memorician to look at them?” Annela said.

“Is that a problem?”

“As far as I can tell, you can find a reason to want access to every piece of information, true or false, ever recorded.”

“It’s not my fault everyone here thinks curiosity’s some kind of personality defect,” Sophie said.

“Cultural flaw, rather,” Annela corrected.

“So I’m not broken, I’m just—”

“Savage. Just so.”

“Thanks a lot, Annela.”

“To get back to your wood fright: I mentioned the bandit ship and the salt frights because of the effort to stamp out such spellwriting. There can’t be that many active frightmakers.”

Based on what evidence? “You really believe that whoever made that ship with the salt zombies might be the same person who attacked Kitesharp?”

“It’s the same be havior, isn’t it? Sinking ships and attacking their crews?”

Sophie nodded. “How to prove it, though, that’s the thing.”

Annela gave a little shoulder twitch, the common gesture that seemed to mean Don’t know, don’t care. “Seems probable enough.”

“It’s probable enough and we’ll never know that are gumming up your court system,” Sophie said. “The point of using me is supposed to be about bringing a little definitely and for sure into the mix. Not to mention case closed.”

Annela tsked. “How much progress have you made? This Forensic Institute of yours promised great things to the peoples of the Fleet, but what you’ve accomplished is little more than a well-trained agent of the Watch might have managed.”

“And yet didn’t.” Sophie didn’t quite hide her sense of insult. It was Annela’s way, she knew, to look at a horse- size success and complain because it wasn’t an elephant. “Anyway, since you ask, I have a proposal.”

“Do you indeed?”

Snagging an apricot biscuit, Sophie pulled out a wad of two-page briefs—a tiny fraction of the Fleet’s ongoing bureaucratic logjams.

“What are these?”

Sophie passed them to Bettona, who started leafing through the pages.

“Five or six times a year, someone disappears from Fleet,” Sophie said. “They desert, or fall overboard, or whatever. And about every three months, bodies turn up in the ocean. Sometimes they’re identifiable, sometimes not.”

Annela nodded. “That’s life asea.”

“These files are petitions by families,” Bettona said. “Requests for death benefits for Fleet recruits who’ve gone missing but are not proved dead.”

“And?”

“I’ve learned that the Fleet takes handprints from its new cadets,” Sophie said. “You’ve even used them a couple times to confirm someone’s identity. But it’s basically been a matter of getting lucky. Some random officer compares the corpse’s prints with the ten most likely missing people. If it happens to look like a match, then hurrah. If not, you’re all ‘Alas, we can’t figure it out.’ Eventually, you get one of these lawsuits.”

“Petitions,” Bettona corrected.

“You can do better, Sophie?”

“Fingerprint identification is an established forensic practice, back home. What if I got the Fleet fingerprint files on the missing people, took the prints of the ‘found sailors,’ as you call them—”

“The bodies, you mean.”

“Yeah. And trained some Watch people so they could create the beginning of a fingerprint bureau?”

“What’s to keep you from falsifying matches?”

“Excellent question,” she said, managing to hang on to her smile. “The answer is, the Fleet gives us the prints of all the missing individuals but mixes them into a number of other handprint samples. Say five hundred or a thousand. They don’t tell us who’s who.”

“You believe you can pick the missing individuals out of the larger pool?”

“Totally.”

“Without magic?”

“Say the Watch gives me a few people and I train them in dactyloscopy. If each of us comes up with the same matches, inde pendently, and if the personnel files they match correspond to missing individuals instead of Joe Random Sailor—”

“That would be convincing,” Annela conceded.

“Convincing?” Sophie said. “Get excited, Annela! It’d be impressive!”

Annela couldn’t quite hide a smile. “This is something you know how to do?”

“Ah. There’s the catch.” She laid out how far they had gotten to date. Bram had assembled information on the procedures. They were both pretty sure Sophie could pick it up. “When the technique originally propagated on Erstwhile, a lot of cops managed to work it out by using textbooks and writing to each other.”

Annela glowered at the apricot biscuits. “Then this is a ploy to get a transit visa to your home nation.”

“It’s not a ploy,” Sophie said. “I don’t ploy. You already know I want to go home.”

“And come back. And go again.”

“I’m happy to bring forensics to Stormwrack, but it’s not all up here.” She tapped her head. “You can’t ask me for help, cut me off at the knees, and then carp about lack of results.”

“Is that what I do?”

“If I can teach the Watch to identify fingerprints, it’ll have tons of other uses. At home, prints are used to solve crimes, not just identify bodies.”

“How?”

Sophie picked up one of the cookies. It was warm, moist, just a bit oily. Then she rolled her thumb over the teacup, leaving a visible print. “You can find prints like this everywhere. The natural oils in our skin make them. This one’s visible, but the Watch can learn to pick up prints that can’t be seen.”

“To what end?”

“A print match can prove where someone’s been, or whether they touched a… say, a weapon. It can place someone at a crime scene aft er they’ve sworn they were never there.”

“Impossible!” Bettona said.

“Seriously. It’s a whole thing, back home. Very reliable.” Reading the doubt on their faces, she scooped up a carefully polished letter opener, made of lacquered wood, with a visible—if smudged—partial print on it. “This is prob ably yours, Bettona. Want me to see if I can prove it?”

“No parlor tricks. Not now.” Annela rubbed her temples. A clock ticked loudly, somewhere close, and the seconds clunking by made it seem as though the older woman was taking forever. To hide her impatience, Sophie ate another of the cookies.

Finally, Annela said, “It seems a more comprehensible procedure than the identity coding you tried to explain.”

“There’s no way you can do DNA analysis here. Anyway, about the sailors’ bodies. Wouldn’t that be good PR? If you start paying out pensions to the families, instead of wrangling over it while they suffer?”

“Mm-m-m,” Annela said.

She’s going to say yes. Sophie was elated. “There are things I have to go home and learn. Plus, I can’t just vanish on my family.”

“What will you bring to Erstwhile, while you’re landing there to acquire esoteric knowledge on uterine tissue and corpse fingers?”

Sophie fought to keep her mouth shut. She could protest that she’d keep Stormwrack’s existence a secret, but Annela would just come back with the inconvenient truth: Sophie had told her brother, the first chance she got. Besides, she was hoping to talk the government here into loosening up on the secrecy. Sooner or later, she and Bram had to get more experts from Earth in on researching this world.

First things first. This was the first step, and she sensed, at long last, some give in Annela.

“You’ve shown this new branch of study has its uses,” Annela conceded. “The Watch has a few lamentably curious work pairs who are excited by your results. If they like this proposal of yours, they’ll recommend it to the court. You would work with the adjudication branch, continuing as you have been, investigating stalled cases that might be resolved by…”

“Evidence? Proof?”

“You would have increased accountability and a higher degree of support. Salaries for you, your memorician, these apprentice fingerprint investigators you ask for, perhaps a clerk or two.”

“What about a role for Bram?” She wasn’t eager to expose her brother to Stormwrack and its dangers, but it wasn’t her call, and she’d promised to ask.

“Depending on the cases in question. You would also be permitted to make periodic visits to Erstwhile.”

“Awesome!” A flood of relief—she almost teared up. Remaining in Fleet had been a gamble, but she’d been afraid to go home until she had official permission to travel between the worlds.

There had always been a chance Annela would never let her go home.

“Before you get too excited, you should know you would have to take the Oath of Service to the Fleet of Nations.”

Wrackers and their oaths and agreements. “Which promises what?”

Annela nodded at Bettona, who said, “You would be, in essence, an agent of the court. You would report to the judiciary, act in their interest, enforce the law, maintain government confidences—”

“Doesn’t sound too major.”

“The consequences, when you break oath, will be severe,” Annela said. “You couldn’t recover from them as you have from your other blunders.”

Blunders. Telling Bram about Stormwrack and magic. Returning when she’d been told to stay away. Getting into a big fight with her birth father over his stupid country of origin and its evil laws—

“What makes you think I’d break oath?”

“You broke your contract with your father within weeks of leaving for Sylvanna,” Annela said.

“Yeah, because you didn’t tell me he was taking me to the Old South slave plantation from hell!”

“Hell… ?”

Sophie sighed. Thanks to magic, she was perfectly fluent in the language of the Fleet, but on occasion she spat out an English euphemism that confused people. Hell, here, was the capital city of another island nation.

Parrish’s island nation.

“Forget it,” she said, unsure if she was responding to Annela or to the inner voice that brought up Garland at every opportunity.

“One can only fight nature for so long, Sophie,” Annela said. “You’ve freely shared your opinion that the Fleet’s values are antiquated and ridiculous. You are bound at some point to prefer your judgment over our rules—”

“How can you say that? I lived just fine in the outlands, as you call them, without ever once going on a crime spree. I barely even break the speed limit when I drive!”

“What will you do when one of your experiments benefits your enemies?”

“I don’t have enemies.”

“No? There are the men who kidnapped and tortured your brother.”

“I—” It was a slap. “Science doesn’t lie. Innocent’s innocent. Guilty’s—”

“I’m not trying to be unkind, Sophie. You’ve said yourself you have no talent for discretion.”

“I said I’m a bad liar. That’s different.”

“Is it? I believe you will always put how you feel before the facts and rule of law. I fear, deep down, you are contemptuous of our system.”

I’m not gonna cry. Sophie toyed with another of the apricot biscuits. “Then why let me go forward?”

“I cannot punish you for oathbreaking until you do it.”

“That’s how it is? ‘Here’s a rope. Let’s see how long it takes you to hang yourself.’”

“We’d say, ‘Here’s a rope. Go loop a sinking anchor.’ But yes.”

This woman is going to be out to get me until the day I die.

“So, what? Can I do this now? I raise my hand and solemnly swear to—”

“Your lawyer must read the documents. We need assurance that you understand what you’re agreeing to. After that, there’s a swearing in every two days.”

“Fine.”

A hint of concern etched itself on Annela’s face. “You shouldn’t do this.”

“You shouldn’t have promised me I’d fail.”

“Striving to prove me wrong is a childish reason to take an oath. But I won’t stop you. Do you want to interview that bandit about frights?”

Reluctance rose again, but Sophie quashed it. “Yes.”

“I’ll file an application. Is there anything else?”

“We talked about me checking out one of those mermaid training drills.” Ever since she’d come to Stormwrack, she’d been diving without a proper partner… emphatically not a trend she wished to continue.

There was an expression, back home: Dive alone, die alone. Sophie liked an adventure as much as anyone, but she didn’t want to become an object lesson in the truth of catchy safety slogans.

“Bette, go find that note of introduction for the diving captain.”

“At once, Convenor.” Bettona disappeared, taking the thumbprinted letter opener with her.

“Well, Sophie? Are we done?”

“Why are you fasting?”

Annela’s head came up, barely showing surprise. “It is,” she said, “an ordeal set by the Verdanii people.”

Religion, then? “Oh. Um. Thanks for telling me.”

“It’s common knowledge, or I wouldn’t.”

“The cookies and nut sticks were all for me?”

“Take them with you. I’m not sure why Bettona made so many, but I’d prefer they didn’t go to waste. Calm seas, girl.”

“’Bye,” she said, bowing herself out.

* * *

Constitution was a ship of bureaucrats, which meant that to her fore there was a law library. It was a bright room, filled with small desks and plush velvet chairs. Half of these were pointed at the smoky obsidian portals of the lounge, revealing a tinted view of the ocean. Two ships were visible to Constitution’s fore. Temperance was the flagship and iron fist of the Fleet, a sharkskinned behemoth with smokestacks rather than sails and almost no glass at all. She was an important symbol of the peace that had reigned between the two hundred and fifty island nations for more than a century. Her captain could sink any ship afloat, simply by speaking its full name aloud.

Step out of line, start a war with your neighbor, and glug, doomed, sunk. A deterrent.

The second ship was Breadbasket.

Each nation had one official Fleet ship, and Breadbasket was Verdanii, the representative ship of Annela’s people. Sophie’s birth mother and half sister were Verdanii. She might be, too, if she hadn’t repudiated citizenship in a weird government hearing eight months earlier. She was officially persona non grata on her birth mother’s home island.

As for her birth father…

No. She wouldn’t think about Cly.

Where Temperance was sharky, Breadbasket was a whale ship of sorts—she had a baleen and a tail. Her masts were live trees, red-trunked palms skirted in sails of woven corn silk and inhabited by jewel-toned insects that served some kind of pollinating function for the crops growing on every available deck of the ship.

She was a great oceangoing farm, in other words—a floating cornucopia, a symbol of her nation’s great wealth. Verdanii was the nation with the most landmass, the agricultural giant of the world.

Rooting in her satchel, Sophie started, as she oft en did, with the notebook filled with questions about Stormwrack and Earth.

Opening it, she paged through, scanning the endless list of mysteries before adding a couple new thoughts: How do you ID uterine tissue in AS? AS, her abbreviation for Age of Sail, was an imperfect description of Stormwrack’s technological state—except when it meant Age of Superstition or Age of Just Plain Stupid.

Are the bugs in Breadbasket’s sails Acrididae or Neuroptera? What’s a Verdanii ordeal? What’s the Verdanii belief system?

Is it an earworm, or am I still hearing that damned ticking clock from Annela’s office?

When she ran out of things to wonder, she pulled out the letter she had already begun to Bram.

The note was written on messageply. As soon as she had written the words, an hour ago, they’d turned up on a twin sheet in San Francisco, where her brother was. He had obviously read them in the meantime; there was an answering message right below the spot where she’d stopped.

Good idea re the archaeologist. Will look over the map and read up on Egyptian sites. BTW: 5.

BTW: “I miss you.” With a number, five out of five. To save messageply, they’d stopped putting the words in.

Sophie found herself smiling. Like him, she skipped the “I miss you” and started with:

5 to you too. I s/b visiting soon if all goes well. AG agrees I need fingerprinting info.

A shadow fell between her and the tinted view of the sea.

Looking up, Sophie found herself staring at the official government representative of Isle of Gold.

Convenor Brawn looked ancient: he was bald, with skin cured to leather by years under a hot sun. His longcoat was made of red velvet, embroidered in gold and, today, belted with a chain of dangling gold skulls. His seven-foot frame was balanced on high boots and a cane that looked like ivory. His fingernails were four inches long—that seemed to be an Isle of Gold thing—and had been artificially straightened to resemble knife blades. Opals were embedded in the nails.

OMG, what do you want? Sophie managed to strangle the impulse to say this.

Take that, Annela. I can be discreet.

Had Annela arranged this? She’d thrown Bram’s kidnapping in Sophie’s face only half an hour before. Now here was the man who’d almost certainly ordered it.

They’d shoved a black pearl under Bram’s thumbnail with a needle.

Rage gnawed at her resolve to keep quiet. To gather herself, she looked past Brawn, taking in the Fleet page attending him. She seemed to be Golder, too. She had extravagantly long red hair, curly and colored black just at its fringes, and enormous brown eyes. She was about Sophie’s age, which seemed old for a page. Maybe she’d failed her exams.

Sophie turned on her camera, out of habit, taking a few shots of them both. Neither of them showed the least curiosity about what she was doing.

“Kir Hansa,” Brawn purred into the silence. “We haven’t met formally. I am Convenor Brawn from Isle of Gold.”

“Uh-huh.” She slapped her notebook shut and stood. If I knew all the nuances of bowing, I could give him some kind of snooty “screw you” half- bob. Out of perversity, she curtsied.

As he was bowing himself, he missed it, or affected to. “May I offer you a glass of wine? Perhaps you prefer Verdanii beer?”

“I’m—um—full.”

“Straight to business then, oui?”

“We have business?”

He pointed a claw at a chair and the girl moved, sliding the seat under Brawn’s bony backside as he perched on its cushion. “I am following your career. This forensic practice, and the court cases you’ve been grooming.”

“Uh… thank you?”

“Isle of Gold is a great nation, and we are fastidious about certain cultural practices. One such is self-reflection. I’ve concluded that you bested me in the Convene eight months ago.”

“I certainly kept you from getting what you wanted,” she said. There had been a plot to disenchant Temperance, to destroy the spell that made it such a lethal ship-killing weapon.

“Indeed. You threw my plans to dry dock.”

She had mixed feelings about having preserved the government’s big military deterrent. But back in the day, when Temperance first set sail, she had driven Brawn’s people out of the piracy racket. The ship had been the instrument by which hundreds of lives were saved.

“It is our tradition to offer someone who has bested us a boon.”

Sophie laughed. “You want to do me a favor?”

“Best me one time, I reward you. A measure of respect. Best me twice, and we are enemies toutta demonde… forever.”

“You kidnapped my brother.”

“Careful. Openly declaring me a foe would be unwise.”

She clenched her fists under the table, taking him in, looking for hints of secrets, of weakness, anything that might tell her what he wanted, or how she could… how had he put it? Best him again.

Brawn’s eye had fallen on Sophie’s book of questions. She fought the urge to close or hide it. He almost certainly couldn’t read English, and there were no secrets there anyway.

Instead of snatching it away, she said, “This is a ritual way of saying… what? ‘No hard feelings’?”

“Yes, nicely put. No hard feelings.” He rolled that around, as if tasting it. “It is an opportunity for both parties to sail away from bloody feud.”

“What if I never collect on the favor but I cross you again?”

“Then, in the moment before your destruction, I shall offer you a kindness. The traditional choice offered is between painless death or payment to your kin. It’s a matter of honor—a concept, I’m given to understand, that you don’t cherish.”

Maybe he was trying to provoke her so they could go straight to the feuding. “What could you possibly have that I’d want?”

“A Golder spouse and citizen’s papers?”

“You want to marry me into the Piracy?” She couldn’t help it—she began to laugh. “OMG.”

“It’s rumored, Kir Sophie, that cased in that self-righteous exterior of yours is the heart of a rogue. It’s said you take aft er ye perre… your father.”

“My father the Supreme Court judge?”

“Your father the killer.”

You are trying to pick a fight. Sophie’s gaze dropped to the book of questions. She should send the guy packing.

But if he knows stuff…

“How about this? I first came here aft er John Coine traveled to the… outlands to buy grenades and assassinate my aunt.”

“What’s that to me?”

She leaned forward. “What if I wanted to know how he got there? The Verdanii seem to think they’re the only ones who—” She wasn’t allowed to talk about Earth explicitly. But Brawn was involved. He had to know. “Who know the route to the grenade store.”

“You’re asking for information.”

“Yep.”

“If I cut you, girl, will you bleed knowledge?”

Gooseflesh rose on her arms. “Do you know?”

He got up, sweeping his lace sleeves over the table as he levered himself upward. “I will do as you ask, soon as you’ve taken the Oath.”

That didn’t go how you thought it would, did it? Sophie thought. She knew why, too: suddenly everyone’s big predictions about what she would or wouldn’t do had fallen into place. Annela figured she’d break her oath because Annela assumed Sophie would think like a Verdanii. Or, perhaps, like a savage outlander.

Brawn had expected her to go into some kind of emo fit, insulting him sufficiently that he could move forward with his vendetta. Now, instead…

He uttered a few words in yet another new language, one with a few tantalizingly French- sounding cadences, and then said, “Sophie Hansa, child of outland, daughter of Sylvanna, I hereby commit. Once this boon is delivered, the two of us may sit in comfort and declare a peace.” With that, he caned himself away, drawing in his wake the curly-haired page—who shot Sophie a glare as she went.

Heart pounding, Sophie collapsed back into the reading room chair. Now she needed more legal advice: if Brawn was willing to tell her something after she got herself oathed up, it might mean she couldn’t legally act on it.

I should just learn the Fleet laws.

When she had first arrived on Stormwrack, it had been by accident. She’d washed up on an island of poverty-stricken fishers, with her half-dead aunt in tow. The island spellscribe had written an inscription to teach her the language of the Fleet.

The spell made her perfectly fluent. She spoke the language without a trace of an accent; she spoke it better than many lifetime residents of the oceangoing city, most of whom had learned it as a second language. All it had cost her was a ripping headache.

She added Learn the law? to a new page in her notebook and began to consider routes that would take her in the direction of her lawyer. In a city where every block was a ship on the move, even the simplest errands were a series of hops, complex exercises in logistics. If you took an airborne taxi here, you could catch lunch while waiting on a ferry to somewhere else. Residents called it footwork: if you could do ten errands in three transits, you were “light on your feet.”

Bram had jotted another note onto the messageply: Can U C a stick figure?

She replied, No. Why?

Him: Trying to project text onto messageply without writing.

Her: Nothing there.

Should she tell him about her encounter with Brawn?

What about now?

She scratched the word Still in front of the “Nothing there” from earlier.

Then, instead of making for the legal quarter, she packaged up Annela’s paperwork, took up a page of cheap, unmagical paper, and wrote to her lawyer, Mensalohm, explaining about the offered deal and her idea of learning the law. She flagged a page and asked him to have it delivered.

She sent a second note to Krispos—her “pet memorician,” as Annela had called him:

Good news—you’re officially on the judiciary payroll. Please read up on Isle of Gold traditions about blood feuds, favors, and challenges. Also, see what you can learn about frightmaking.

She took a moment to savor that. Krispos was a magically enhanced speed-reader with perfect recall. He had been foundering in a state of impoverished semi-unemployment for about five years. Even the prospect of having a real job within Fleet made the old fellow tear up.

She’d done all she could aboard Constitution. Taking her note of introduction from Annela, she caught a ferry to Vaddle, the diving vessel.

Excerpted from The Nature of a Pirate © A.M. Dellamonica, 2016